Brands

When Will Content Marketing Count as Prestige Art?

The art world’s relationship with content marketing is in the middle of a vast sea change. Tech giants like Apple, Amazon, and Facebook have begun to reshape themselves with content, in the mold of media companies like Disney. The business world is following their example. Mainstream media companies and marketing firms are even starting to resemble each other.

As content marketing, product placement, and art blur together, there’s a space opening up for brands to make something unexpected. Provided, of course, it doesn’t come off like “My Journey to Self-Love, Sponsored by the J.M. Smucker Company and its Major Subsidiaries.”

Apple’s shifting relationship with product placement is s a microcosm of what’s happening in the industry. For years, the tech company quietly made deals to seed images of iPhones and Macbooks in popular television, but Fox has been running a message at the end of TV episodes featuring Apple products that cites “promotional consideration sponsored by Apple.” Now that Apple is developing its own TV shows, its executives are reportedly “squeamish” over the ways products will appear in programming.

Now that brands are creating their own content, many don’t need to pay for placement. In 2015, a movie about a toy brand (supported by that toy brand) was nominated for an Academy Award. The Lego Movie did not end up winning Best Original Song, but Lonely Island performed “Everything is Awesome” alongside several dancing, life-size mini figs. There wasn’t a huge to-do about The Lego Movie being an extremely successful bout of content marketing, partially because consumers aren’t always aware of corporate interests, and partially because the movie was just so damn good.

https://vimeo.com/318074749

We’re seeing even greater strides toward brands making content that’s recognized by prestigious, mainstream institutions. This spring, a documentary about a gay choir produced by the home-share platform AirBnB premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival. What’s more, an original off-Broadway musical from Skittles was rumored to be in line for a Tony nomination, though it was eventually snubbed.

So, when will the first piece of content from a brand win mainstream accolades from a prestigious institution?

Who decides which content is prestigious?

It’s conceivable for a brand to produce a popular piece of art, and it’s possible for a brand to create good quality art. Consumers decide if something is popular. As long as the content is entertaining, the source isn’t as important.

Unfortunately for brands, defining prestige is up to the artists, critics, and influencers in the creative industry—you know, the folks who cringe when they hear the word “brand.” However, as that old guard tries to protect an outdated definition of prestige—being resistant to streaming networks and web series, for example—modern audiences are showing more flexibility.

Most modern audiences understand that entertainment is a business. Look no furhter than the widespread discussion on social media that erupted when Disney bought Fox. Any big Star Wars or Marvel fan knows their favorite characters are as much data points on a Disney spreadsheet as they are beloved heroes. You could argue that concepts like The Avengers or the Jedi, proliferated as they are across TV, social media, merchandising, comics, amusement parks, and video games, are just brands.

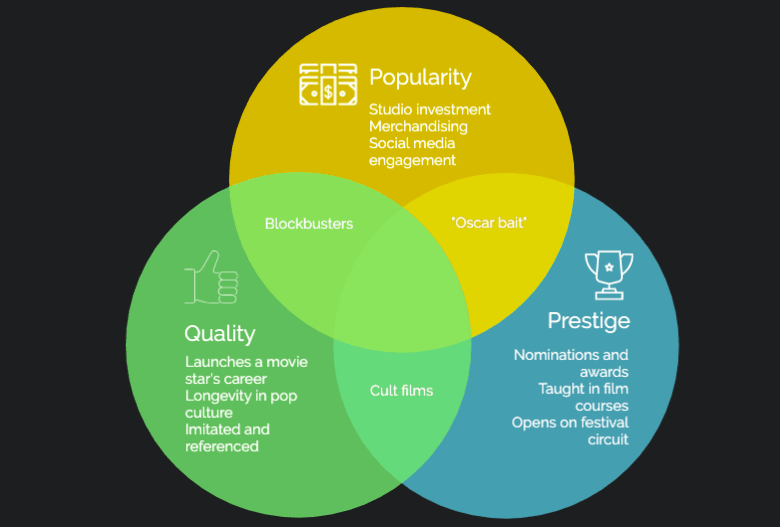

But that still leaves the lingering question: When will the first piece of prestigious branded content hit the scene? Using film as an example, I’ve mocked up a Venn diagram to explain where popularity, quality, and prestige intersect. Notice there’s nothing in the center—my best guess was Black Panther, but I welcome suggestions. Singin’ in the Rain is another possibility.

If a movie is popular with the masses and of pretty good quality, it’s usually not considered high art. See action comedies, superhero movies, and Star Wars. Meanwhile, if a movie is of good quality and considered prestigious, it probably didn’t blow the doors off the box office or earn mainstream appeal. See quiet indies, experimental art films, and period dramas. Finally, if a movie is popular with the masses and the Academy without actually being good quality, it is what one might call “Oscar bait.” Examples include The King’s Speech, Bohemian Rhapsody, Green Book, Argo, The Blind Side, and the definitive installment, Crash.

A brand could aim to make Oscar or Emmy bait content, but they could also try and create an irreverent, cult-beloved piece of art—the Skittles musical was an earnest attempt at that.

Rethinking the ROI of prestige

Charming the critics and art snobs of the world with content marketing isn’t an impossible feat; it’s just unprecedented. For marketers, achieving prestige isn’t a necessary objective, given that everything in their industry needs to hinge on measurable ROI. There is no measurable ROI for prestige or cultural impact or artistic clout—that’s kind of the point.

But what if a content marketing team hit the zeitgeist with a great piece of art at exactly the right time? It would have to exist purely for brand awareness, and the art itself couldn’t have any messaging about the brand—all the promotion and brand association would have to be implied. And it’s alright to imagine a marketing team developing a great film or TV pilot or novel—so many popular pieces of media are the product of fifteen songwriters or eight screenwriters, a gang of producers, and a director.

We may very well see a truly prestigious piece of content marketing in the next decade, whether that means it’s accepted into a film festival or wins a highbrow creative award. If a brand has any shot at creating art (as opposed to just marketing), it’ll be an argument for the melding of those two ideas. We know that popular franchises, characters, and creative projects can turn into brands, so why not the other way around?

Get better at your job right now.

Read our monthly newsletter to master content marketing. It’s made for marketers, creators, and everyone in between.