Brands

How Contently Defeats ‘Comment Bullies’ and Promotes Valuable Reader Reaction

This is the first post in the “On The Couch With Contently Series”, featuring conversations between Contently co-founder Shane Snow and managing editor Sam Petulla about content-related issues.

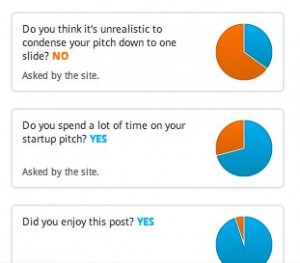

Sam Petulla: As some savvy Content Strategist reader may have noticed, we use a different commenting system than some readers might be used to, called Urtak. At the end of an article, the system prompts a reader with specific questions, the total responses to which are displayed in pie charts, rather than allowing for open-ended discussion.

Why did we go with Urtak instead of your typical let ‘er rip comment template?

Shane Snow: There are two main reasons we use Urtak instead of comments.

Shane Snow and Sam Petulla at Contently.

First, it’s general knowledge that the majority of comments on the web are either negative/unhelpful, spam, or self-serving promos that don’t move discussion forward. The kinds of people who are motivated to comment are typically either angry or selling something – like the kinds of people who are most eager to get on the microphone at a conference.

Second, most people – and the most representative part of your audience – don’t comment at all. Because you just click yes or no buttons to answer questions, Urtak, in my experience, gets 10-100, sometimes 500 times as many responses as comments [ex: look at this post = 157 Urtak reactions, 0 comments].

So, with Urtak you kill two birds: silence the unhelpful comments and increase lean-forward responses to your content.

And since Urtak is quantifiable (everything is yes/no), you can gain pretty incredible insights that you’d miss if you had the problem some news sites have, which is too many comments for digestion or needle-in-haystack insight retrieval.

Also, you can allow community members to ask their own questions. Not a lot of people will do this, but comment bullies tend not to do it either.

Petulla: What do you think a commenting system can offer for a reader? I tend to think of them as looking for needles in haystacks. Nine times out of ten you just kind of shake your head or gloss over a comment, but then that one time you do find a link or an opinion that puts you in the back of your seat and makes you glad you looked further down the page. Is there a risk of losing this?

Snow: I can’t think of a time this has happened to me in the last year, so no. That said, there are certain sites, with certain communities, that have managed to foster good comment environments with lots of discussions that aren’t overwhelmed by hostility and the general scum of mankind.

But I can count them on one hand. AVC and Reddit (believe it or not) come to mind.

Petulla: The other cool thing about Urtak is that you see other users’ replies in an aggregate form. So you learn something about other people who read a blog, and you see how their opinions conform to your own. Do you think content strategists can learn from this type of commenting system?

Snow: Content strategists can learn more from the quantitative data output you get from Urtak than through comments. Because the average person will answer multiple questions, you end up building a data profile that can be used for cross-tabulating insights.

For example, in a recent Urtak, I discovered that 72% of my Facebook audience is under 30 years old. Cross-tabulating that with another question, “Is man-made climate change real?,” I determined that those under 30 are more likely to believe climate change is happening than those over 30 (77% of under 30 say yes, vs 67% of over 30).

For example, in a recent Urtak, I discovered that 72% of my Facebook audience is under 30 years old. Cross-tabulating that with another question, “Is man-made climate change real?,” I determined that those under 30 are more likely to believe climate change is happening than those over 30 (77% of under 30 say yes, vs 67% of over 30).

You end up learning interesting things about your audience which may differ greatly from a general audience, and that can fuel future coverage and content ideas.

Petulla: I have to confess that I am a bit of a utopian when it comes to comment systems. I see most comment fields as existing in a kind of state of nature for a productive information commons, with the possibility of them all becoming gardens of earthly delights. I think eventually, we will discover the right way to reward and fend off the comments we seek and want to avoid, using the right mix of authentication, prompting and gating.

It seems like some small blogs — think Fred Wilson’s or Marginal Revolution — have pretty healthy comment sections, whereas others, think of YouTube, are playgrounds for animosity. Could you see YouTube going to a pure Urtak-based system? Or do you think some other mixture of real-name commenting and an Urtak-system would work?

Snow: Comment utopia will be achieved around the time human utopia is achieved, or around the time we ban idiots from the Internet. It can happen, but it’s usually a circular thing. You have to have motivation and payoff to want to take the time to comment in the first place.

A good community reinforces the payoff, but getting one started is tough. Fred Wilson’s blog is great, but people started commenting in the first place because they wanted to kiss up to the man with all the money. Luckily, Fred did a great job of tending his community, and now there are genuinely interesting discussions, friendships made, and so on.

It’s hard to see that happening many other places, and the motivation question is really the issue that prevents it. I have no incentive to comment on most content. A lot of times, I have no time to comment, much less worry about crafting a great response that some troll wont lambast me for. People have lots of incentives not to comment.

The problem with YouTube, aside from garbage comments (although some are hilarious), is exemplified in the extreme on Justin Bieber’s “Baby” music video. There are over 8 million comments. No human could read all of those. If YouTube used Urtak, and let users ask and answer binary questions, those 8 million comments would probably be 800 million points of data and an incredibly valuable feedback set on the content and audience.

Petulla: Recently, a number of tech blogs circulated a study saying real-name authentication does not improve the quality of comment systems. This seemed odd to me because almost all these same blogs previously preached the virtues of going to a real-name system. Should publishers think of going to this type of system if they are not ready to take the Urtak leap?

Snow: There’s one spot we use comments on The Content Strategist, and that’s on feature stories we think have a higher chance of getting a good discussion going. Note that discussions rarely last more than 2 comments deep, even on stories with tens of thousands of page views.

Real-name authentication may not improve comment-to-page-view ratios or quality of comments, but the Facebook comment system actually spreads your content when users comment. For that reason, if I were to pick a comment system and pray for comments, I’d at least use Facebook’s.

With an anonymous comment system you may get some people who are scared to comment under their real names, but those are rarely value-add comments (and I dislike sissies who won’t stand behind what they say). Whistleblowers have much more high-impact options for anonymous tipping than comment sections of websites, so I wouldn’t be afraid of hindering democracy by disabling anonymity in your comment section.

Petulla: What I think sets Urtak apart is the prompting. Often, the first or second question in an Urtak comment-box is something like: “Do you like Zombie films?” What do you think of this? Is it a time-waster? One nice thing it does is it puts you a little out of your frame of mind. When you finish an article, sometimes you get to the bottom totally fuming or totally inside your own head, and the comment box is this sort of open window where you can just vent whatever first feeling is on your mind. Then the next guy does the same thing — sometimes at you. Then the next, then the next. That seems unproductive.

A major takeaway from behavioral economics is that if you give people cues or a default setting, people’s attitudes and choices shift a lot. So if somewhere between commenting you are reminded you like Zombie films, you might be less likely to channel your rage at anonymous people on the internet. Urtak seems to be up to some of that.

Do you think open-ended comment systems can be improved somehow using this type of idea? Maybe just by using sentiment-detection? Thoughts?

Snow: I recently saw the most civil conversation about politics I’ve ever seen on Facebook. Every time the discussion got heated, the guy whose wall it was would write a funny message or say something like, “Just to keep things in perspective, guys, here’s a cat riding a dog on a trampoline.” It defused the tension, and that’s why I think random questions in Urtaks help keep people a little more rational.

Also, there’s no hedging in a yes/no question, so you end up really having to think about what you believe. I’m not sure how comment systems could apply this principle (aside from changing comments from qualitative to quantitative feedback mechanisms like Urtak), but I think content creators who use comment systems have the opportunity to foster such environments with their own prompts and by interjecting and adding to comment threads themselves.

It’s a lot of work, and it can be both infuriating and depressing to dive in and try to referee a comment thread (infuriating because people can be jerks; depressing because people can be idiots). But if you can solve the motivation-to-comment problem, being an active comment moderator can make the difference between a civil discussion and one that chases value-add commenters away.

Get better at your job right now.

Read our monthly newsletter to master content marketing. It’s made for marketers, creators, and everyone in between.