Brands

This Is What Content Marketing Looked Like in the 1800s

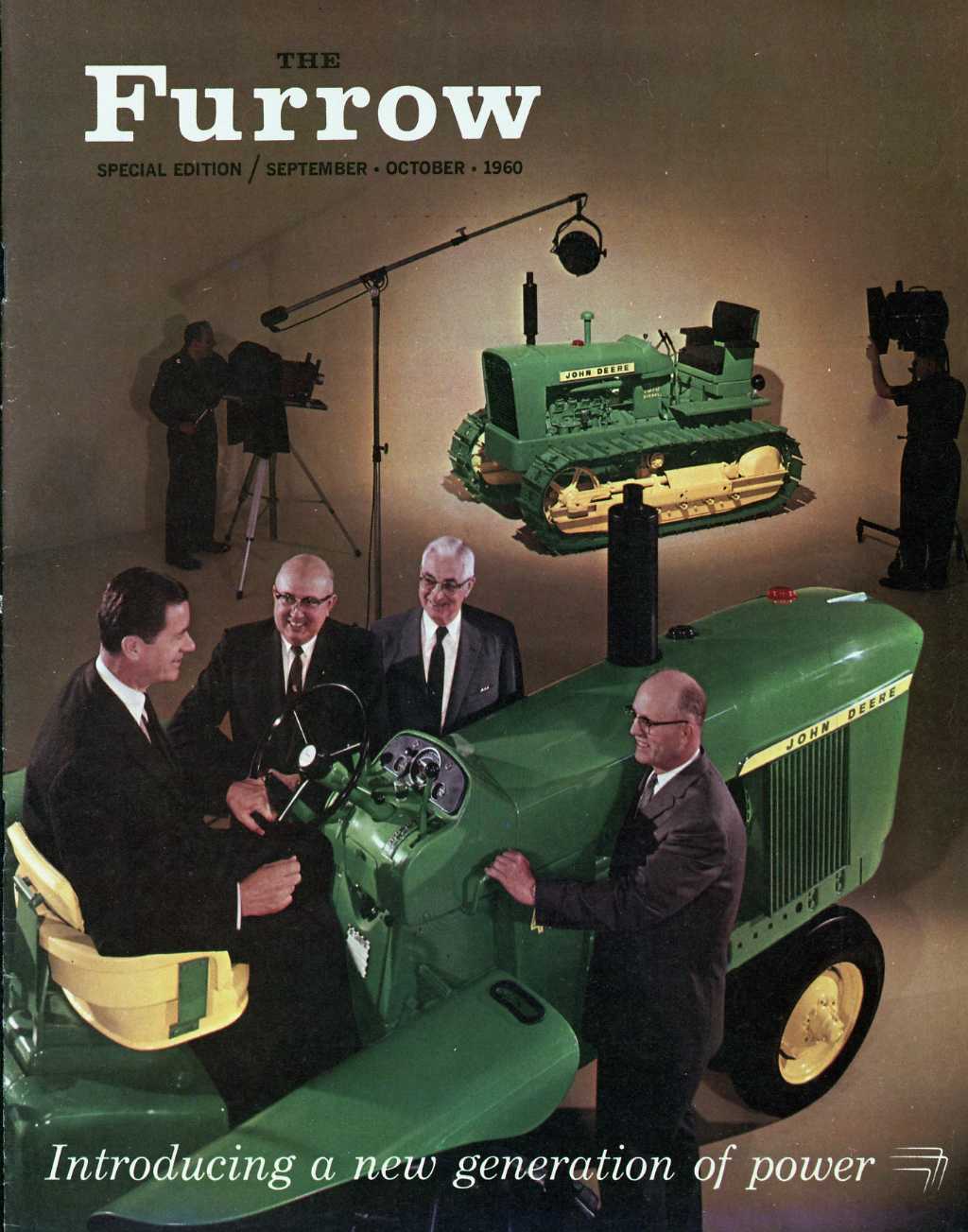

The Furrow, John Deere’s magazine for farmers, has been in print since 1895. A few years ago, we published an article about the esteemed magazine, looking at how it’s managed to stay relevant in print even as digital outlets started to dominate.

In marketing circles, The Furrow is a legendary entity, the Adam of brand publishing. In 1912, it had a peak circulation of more than 4 million readers. To take this origin metaphor to an absurd extreme, we’re excited to give you a glance at Eden.

Recently, as I searched through old emails, I realized there were a lot of insanely cool editions that we never published in the original piece. It’s the first week of January, and I don’t really feel like doing real work yet, so I thought I’d share them.

According to Neil Dahlstrom, John Deere’s manager of corporate history, the publication was a pure advertorial in its earliest days. This edition from the spring of 1897 is a pure sales pitch for plows, which kind of reads like an email from a Nigerian Prince: “We have some LEADERS which it will pay you to examine early, and we believe we can suit you in quality and price.”

Sure thing, John, let’s roll!

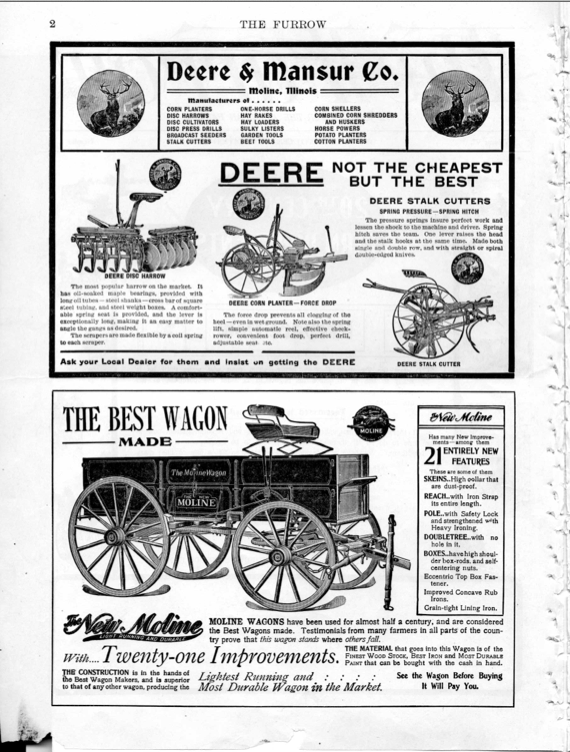

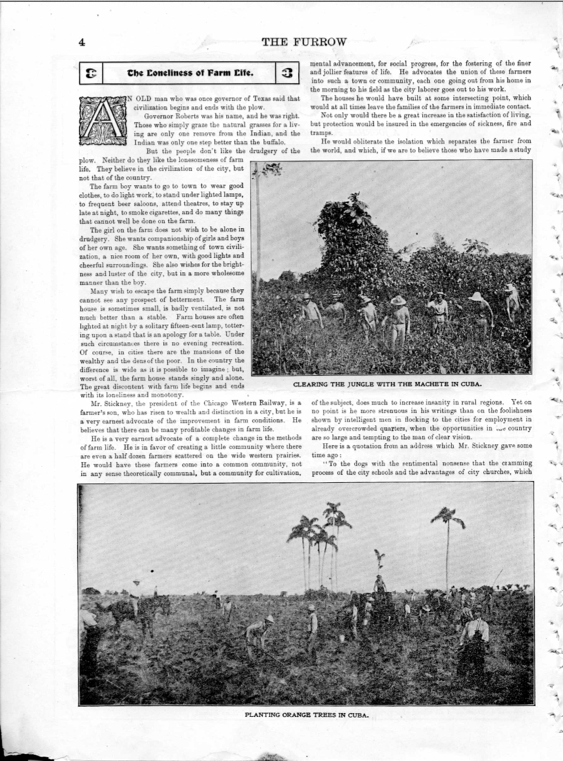

By the turn of the 20th century, The Furrow had started experimenting with narrative storytelling. After making the sales pitch up front in the first two pages, this issue from 1901 delves into impressive pieces of narrative storytelling.

“The Pearl of Antilles” is a compelling story about farm life in Cuba. Imagine how it would have struck the Americans who received the magazine at the turn of the century. It’s so glorious that I had to transcribe one section:

The Pearl of Antilles

“Man, in his attempts to attain those things necessary to his existence, and which the Almighty provided for him at the birth of the world, first seeks a place for habitation, then he proceeds to the fields and forests to find himself the pleasantest location, surrounded by those gifts of nature most suitable and from which he may, by honest toil, secure sustenance for himself and those dependent upon him.

In no country or clime under the skies can such a perfect and ideal realization of that which he most wants be met with more satisfactorily than in the Island of Cuba. He must not expect to let his ambitions and energies decay. He must work here the same as he should elsewhere, but the same amount of labor expended on his island plantation will net him greater gains than in any locality I know of.

Farming is carried on in Cuba by the natives pretty much the same today as it was when old Spain’s pioneers struck their sharp iron pointed sticks into the land, following the same with their old Spanish, or Cuban turn-plows, and it is difficult, almost impossible, to convince the people that their antiquated implements are centuries behind those of today. However, many of the more progressive and intelligent are adopting and using the innovations that are gradually being introduced, among which is the modern plow. I see quite a number of plows of all kinds brought to the island, but with one exception they are discarded with maledictions on those to whom they paid cash for something “no good.” The exceptional plow I speak of is the “Deere Disk,” which, according to the testimony of those using or seeing them used, without hesitation and with pleasure, say it is the only satisfactory plow on the island. A number of American and several prominent Cuban planters are using the Deere plow, in some instances to the exclusion of all others, after giving a fair trial to each.

Damn, they don’t make copywriters like that anymore. (Mostly because they’re all in Sarah Lawrence’s MFA program, starving to death.) This article legitimately resembles a Hemingway short story, and the artful plug for John Deere is a masterclass in how to integrate a plug without disrupting the flow of the narrative. They’re saying “screw your plow, ours is awesome,” but in a very classy way.

“The Loneliness of Farm Life” is another elaborate tale that contemplates the life of a farmer. Though mildly racist in parts, it has some gems that remind me of Tolstoy quotes I’ve considered tattooing on myself at one point or another: “But the people don’t like the drudgery of the plow. Neither do they like the lonesomeness of farm life. They believe in the civilization of the city, but not that of the country.”

The magazine, as a whole, is amazing to dig into. (I uploaded one edition from 1901 to Contently Document Analytics here, and another one from 1903 here.) I wonder if our great-grandfathers sat around and argued over the best way to attribute the ROI of direct-mail campaigns?

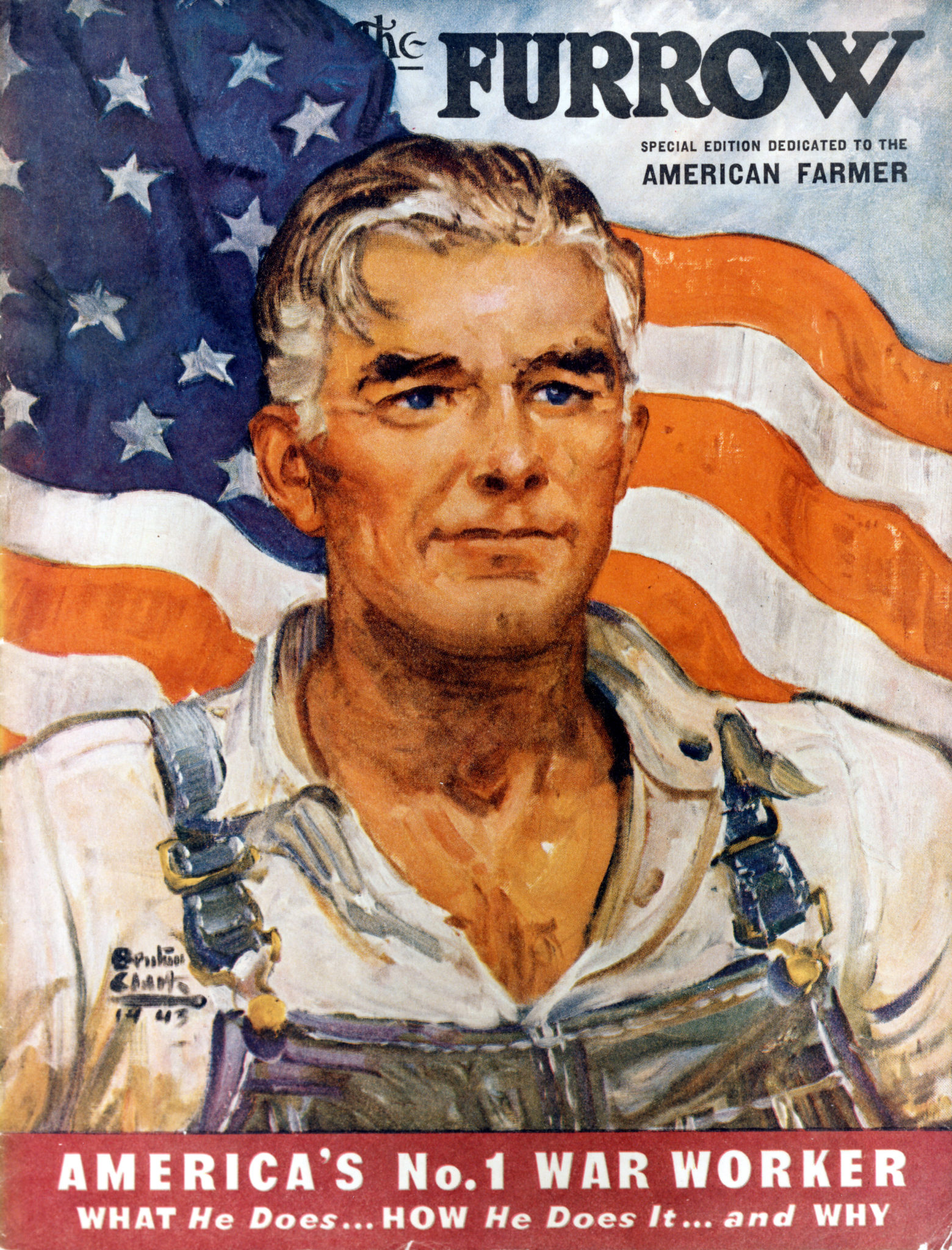

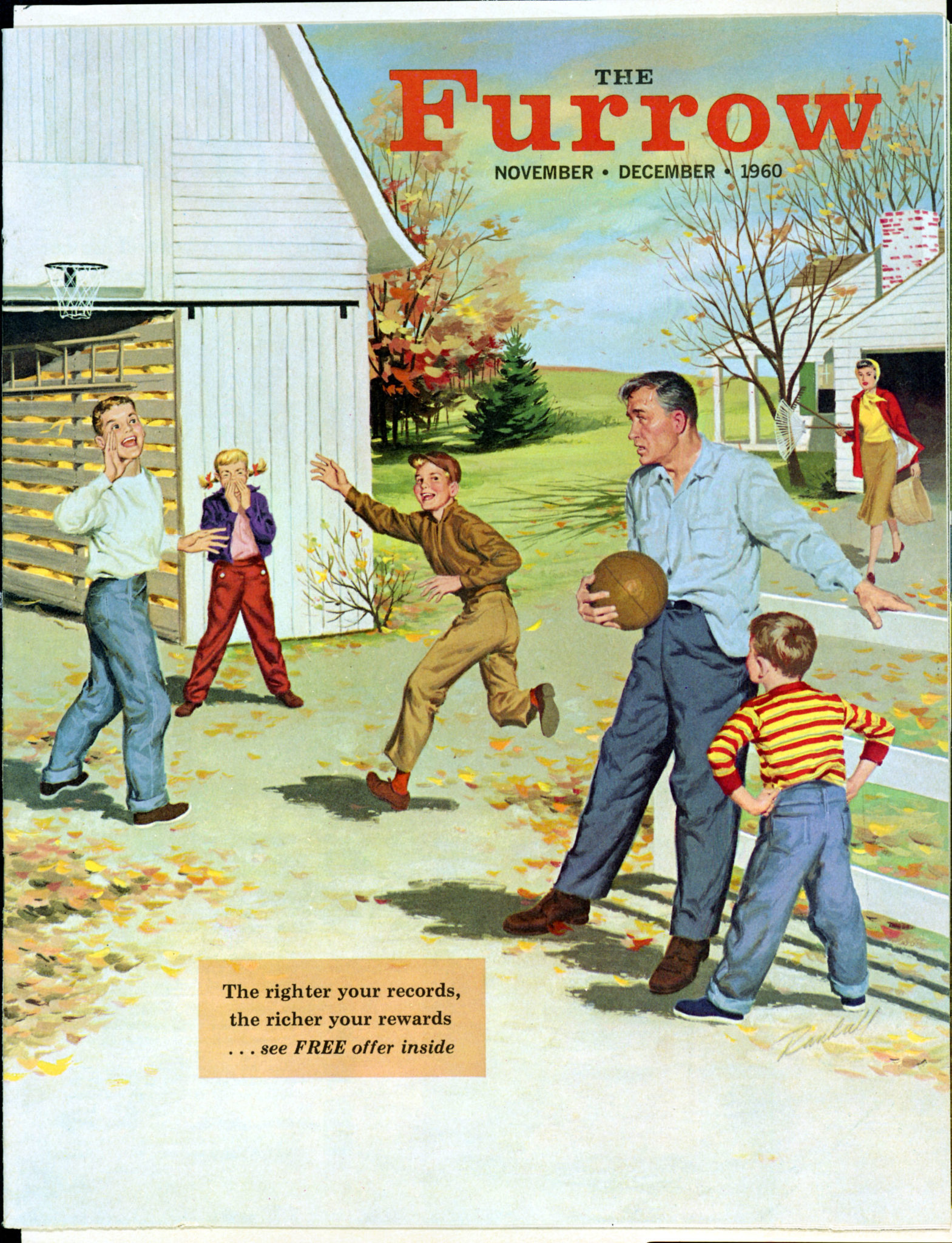

Sadly, the Hemingway era for John Deere didn’t last forever. By the late 1960s, The Furrow had evolved to a full-color magazine and changed its name to “A Journal for the Progressive Farmer.” Judging from the covers, progressive seems to be a code word for studmuffin. (Which, in turn, is a code word for an attractive manly man.)

The Furrow is still in print today as the world’s longest-running brand publication, but it’s also online on a gorgeous site with lots of white space and surprisingly few pictures of tractors. They’ve since ditched the short stories filled with existential dread, but I for one would love to see them bring them back. I’ve never ridden a tractor in my life, but I have written a lot about content marketing. A boy can dream.

Get better at your job right now.

Read our monthly newsletter to master content marketing. It’s made for marketers, creators, and everyone in between.