Media

Why Major Institutions Lost Public Trust, and How They Can Gain It Back

In 1994, a high-ranking FBI officer was murdered. He had leaked information about a government cover-up to a couple FBI agents willing to investigate—and paid the ultimate price.

His dying words were, “Trust no one.”

The murdered officer, codenamed “Deep Throat,” was actually a fictional character in the Season 1 finale of the television show The X-Files. (He was based on a real informant with the same codename who helped reporters break the Watergate scandal.) As a 10-year-old when this episode premiered, I was appropriately devastated.

Deep Throat’s fictional assassination by his own government came at a historic time in America. Fox launched The X-Files when faith in the American government had dropped to an all-time low. In fact, it came at a time when American faith in all institutions was at a low after falling steadily since the 1970s.

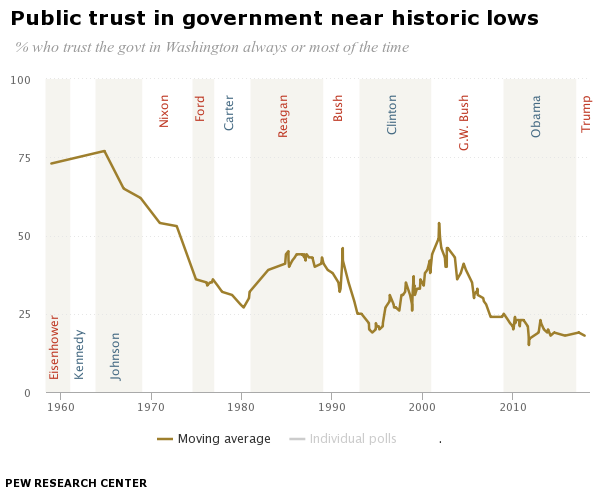

That trend, which X-Files captured in its decade of paranoid television, has continued until today, save for a brief climb in the late ’90s during the economic boom and a spike after 9/11. Per Pew Research’s annual survey, which asks people about their level of trust in government to do the right thing “most of the time,” here’s a snapshot of public confidence in the U.S. government over the decades:

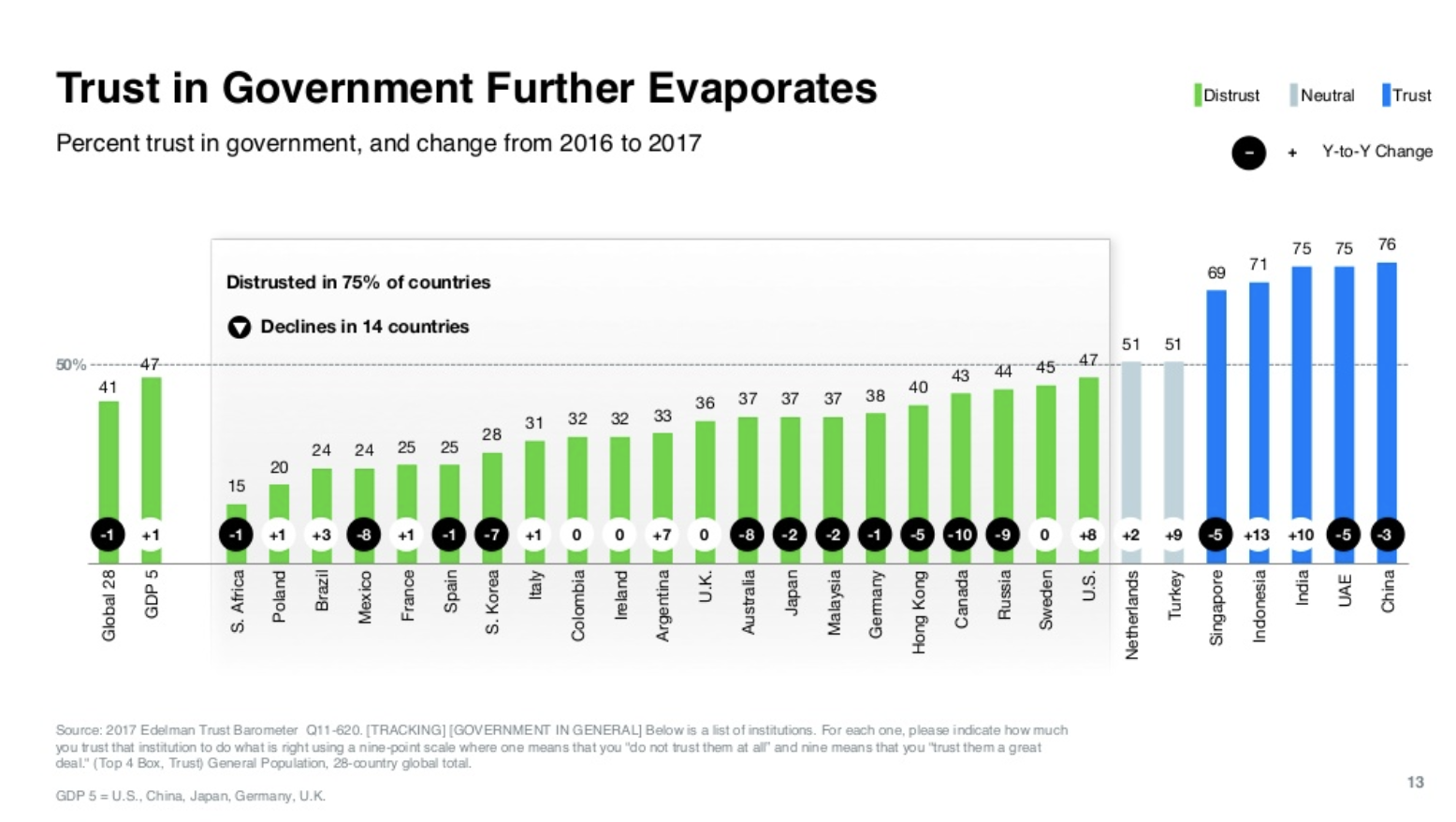

By another measure, the Edelman Trust Barometer, which measures trust that various organizations and people will do the right thing on a scale of 0–100, three-quarters of governments around the world are distrusted by their citizens:

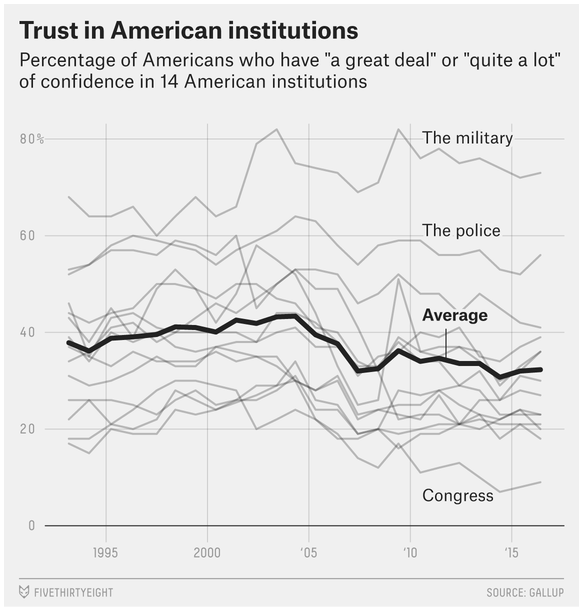

But it’s not just government. According to Gallup’s survey about public confidence in various institutions, administered every year since 1958, we’re losing trust in just about everything.

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy argues that institutions have a social purpose and transcend individuals by creating norms and rules that people can count on. Basically, institutions are the building blocks of society. If we lose trust in an institution, dysfunction will follow until that institution is replaced by something else that can govern our behavior and make life predictable.

As a journalist and the founder of a company that helps businesses publish information, these charts are particularly vexing. (As of 2016, only 20 percent of Americans trust newspapers, per Gallup.) Distrust in the press threatens society. Democracy needs information to expose corruption and keep people informed. And distrust is certainly bad for business, bad for the economy, and so on.

There are surely bad actors in both the business and media worlds who don’t deserve our trust. But there are plenty of good actors, too. Knowing which of these to trust is more difficult than ever. And for those of us with a stake in our own institutions, gaining trust is more paramount than ever.

A Brief History Of (Losing) Trust

In 1977, political scientist Ronald Inglehart proposed that people lose trust in authorities and organizations as they become wealthier and less concerned with basic survival.

This theory may explain some of the general decline, but even the wealthiest people still trust some things—the power grid, capitalism, their therapists. The rest of us probably trust some brands. (I put my faith in Starbucks to not poison me no matter where I am in the world.) In many cases, it’s good to be skeptical. But when we look at the history of our most important institutions, there’s a simpler explanation for why we lose faith, even for institutions that helped us out in the past.

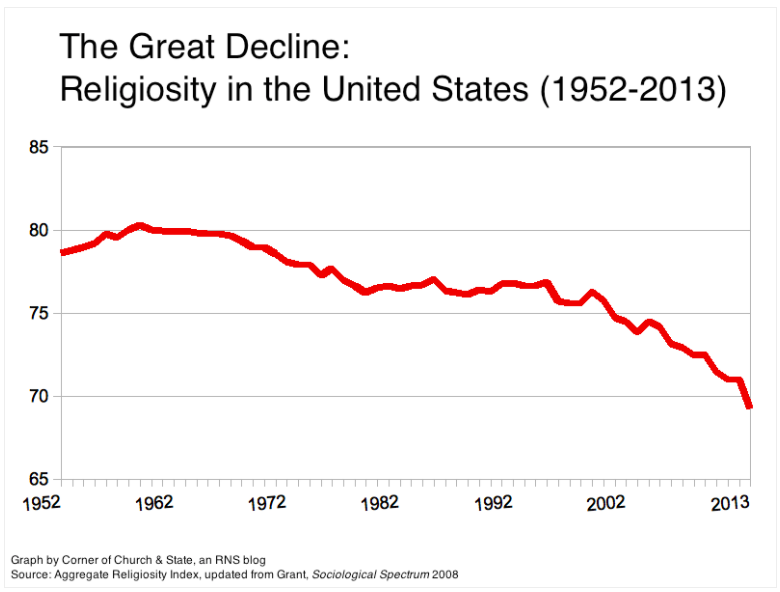

Before the industrial revolution, most societies put their trust in religious institutions. Yet over the years, fewer and fewer people have trusted religion. This resulted in the splintering of religious sects—protesting the religion that betrayed your trust by forming a new religion—which eventually led to more people abandoning religion entirely.

Then we generally believed in democratic governments. But trust in that institution eroded as well. We became more cynical that the democratic process was truly working.

As faith in government rose and fell, we turned to business for a bit until that deteriorated. Certain industries, however, managed to keep our trust even as the general business world lost it. These included banks, healthcare, education, charities, and the mass media. They were seen as more noble, more “in it” for the good of society. We now distrust all of those too; it just took a while longer. (See the charts above!)

Losing trust in an institution (or an individual) stems from betrayal: When we feel lied to, taken advantage of. In the case of all the institutions I mentioned above, the loss of trust boils down to one thing: greed.

The pattern here is pretty simple. Religious leaders broke laws, misused funds, and showed that what a church said didn’t square with reality. Political leaders made decisions based on money rather than the good of the people. Financial companies got rich at the expense of poorer people and the economy at large. Media companies tricked people with misinformation or sketchy information meant to increase attention and revenue. I could go on a lot longer.

Fortunately, both science and history show us how we can get trust back once more.

How We Can Build Trust Again

This year, eight professors from U.S. universities published a study in the journal PLOSone that offers some instructive insights on institutional trust. The professors decided to send 185 college students updates about a couple of government agencies they knew very little about: Nebraska state water regulators.

Every three months for a year and a half, students received news about the regulators. Compared to a control group, respondents who got the updates reported having more trust in the water agencies even though their overall trust of the government didn’t improve.

The conclusion from the study is simple yet important: Information and transparency build trust. The more we learn about what’s really going on inside an organization, the more favorably we judge it compared to whatever category it fits in.

However, the study also found that people who were pretty skeptical about everything in life didn’t report a big boost in trust in the water agencies just from learning more about them. Overcoming this general mistrust takes a little more.

According to Paul Zak, Claremont University neuroscientist and author of Trust Factor, we need to develop an emotional connection to regain trust or form a trusting connection with a person or institution. We can do this by engaging in activities that release the chemical Oxytocin in our brains—the neuro-mechanism by which ancient humans decided that other humans were safe enough to work with and trust. The behaviors that induce Oxytocin production include hugs, acts of kindness, and—get ready for it—telling emotional stories. (See Dr. Zak’s TED talk about Oxytocin here; it’s great!)

According to the Edelman Trust Barometer study, three-quarters of people believe that “a company can take specific actions that both increase profits and improve the economic and social conditions in the community where it operates.” We think companies are capable of doing business without betraying people.

What all this research tells us is if organizations are not just transparent about what they do, but forthcoming about how and why they are doing it, they’ll build trust—even in industries that have lost credibility.

We built our trust in all of our institutions, from religion to banks to newspapers, based on the stories they told us. Now let’s start telling more of them. Let’s start telling true ones.

Image by iStockphotoGet better at your job right now.

Read our monthly newsletter to master content marketing. It’s made for marketers, creators, and everyone in between.