Brands

How Social Media Sentiment Impacts the Presidential Campaigns

As part of the Content Campaign ’12 Series, The Content Strategist examines content published by the presidential campaigns as part of their strategy to win November’s general election.

Social media analysts appease our dark desire to know what others think about us—at least in the public social media sphere.

Analysts scour social networking sites to get people’s opinions, positive or negative, and find out what they’re saying about a certain person, business or idea.

Analysts scour social networking sites to get people’s opinions, positive or negative, and find out what they’re saying about a certain person, business or idea.

Sentiment analysis, as it’s called, is a natural fit for the presidential campaigns, an area fiercely polled, plotted and politicked.

This election season, analysts are further zeroing in on the most hallowed of all ground for candidates: swing states and, by extension, their oft-sought after yet still mysterious undecided voters.

This week, The Content Strategist spoke to two firms specializing in sentiment analysis — Attensity and SDL — and highlighted their research to get a better idea of the plusses and pitfalls of gauging sentiment.

How does it work?

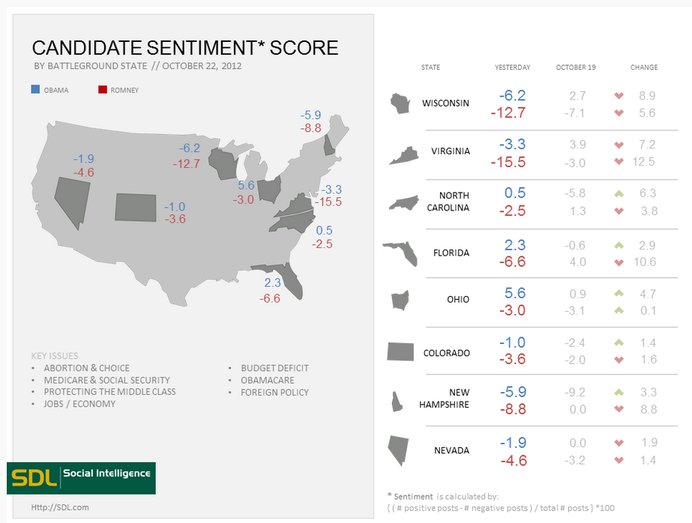

Both SDL and Attensity use proprietary software to gauge social media sentiments for the candidates, especially in swing states. For this specific analysis, Attensity monitored opinions on Twitter, while SDL used Twitter, Facebook and the “blogosphere.”

Both SDL and Attensity use proprietary software to gauge social media sentiments for the candidates, especially in swing states. For this specific analysis, Attensity monitored opinions on Twitter, while SDL used Twitter, Facebook and the “blogosphere.”

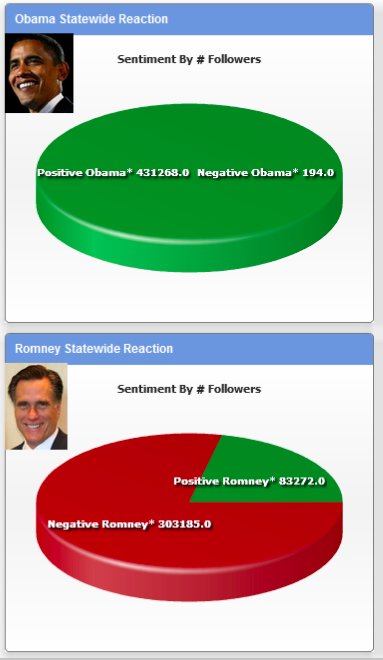

Attensity creates a pie chart to show the relationship of good and bad tweets out of total “sentimented” tweets, while SDL assigns a percentage point: positive posts – negative posts / total posts x 100.

According to Attensity’s Vice President of Strategy Michelle de Haaff, the software goes to great lengths to account for all the different names for candidates — pres, Mitt, Obama, Gov. Romney — as well as subtleties in sentiment. “Good job Romney” counts as positive, while “Good job Romney, you moron” is decidedly negative. Something like “The candidates are debating” is neutral and discarded.

What does sentiment analysis say?

Both sites showed Obama to have a distant lead in the sentiment campaign — if not so distant in the real one.

Romney, on the other hand, is no social media darling. Although it’s tempting to say that means he’ll be unpopular among voters, there are a number of reasons why he might be less popular on social media than in voting booths.

For starters:

- Obama has been using social media — and using it well — since his first presidential campaign. Romney came later to the game and has fewer followers across the social media landscape. Obama has 21 million Twitter followers compared to Romney’s 1.5 million; Obama has 31 million Facebook likes while Romney has 10.5 million.

- Romney’s followers are older than Obama’s. Obviously, people who didn’t grow up with social media technology are less likely to use it.

- Liberals are more active than conservatives on social media.

According to Attensity, Obama predominantly had positive sentiment geared at him, with “Go Obama” being a top tweet sentiment topic. Romney, on the other hand, had a higher rate of negative comments, specifically regarding his ability to handle foreign policy.

SDL found the main topics discussed in sentiment to be abortion, Medicare and Social Security, protecting the middle class, jobs and economy, budget deficit, Obamacare and foreign policy.

Who is on social media, anyway?

According to a recent Pew study, social networking users are more likely to be young, female and liberal. Pingdom maps out social media demographics for a number of sites here. (Note that the average is not as good a measure as median, because outliers can skew the average up or down.)

Also keep in mind that the demographics of the average Internet user is not necessarily the same as the average voter.

Do people vote the way they tweet?

Attensity includes a rather interesting measure: Whom people say (on Twitter) they are going to vote for. What is most startling (and better illustrated by the study of the second debate) is that voting intentions don’t necessarily match up with negative/positive sentiments.

For example, during the Oct. 16 debate, Iowa Twitter users had nearly all positive things to say about Obama and mostly negative comments about Romney. However, they were way more likely to state their intention to vote for Romney.

What this drives home is that, although sentiment can indicate the popularity of a candidate, it isn’t a surefire way of seeing who will win. After all, many other factors are at play.

The Twitter users who state their voting intentions aren’t necessarily the ones saying positive or negative sentiments. Also, saying you’ll vote for Obama on Twitter is not the same as showing up and voting at the polls.

Actions always speak louder than words.

Get better at your job right now.

Read our monthly newsletter to master content marketing. It’s made for marketers, creators, and everyone in between.