Brands

Article or Ad? When It Comes to Native Advertising, No One Knows

Native advertising—articles paid for and/or written by a brand that live on a publisher’s site—has emerged as a powerful and popular new advertising tool over the past few years. Media companies like BuzzFeed, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and The Atlantic have all invested heavily in the creation and distribution of native advertisements on behalf of brands, with many charging over $100,000 for a native advertising campaign.

But with it has come controversy, with many debating whether native advertising is fundamentally misleading readers by cloaking an advertisement in the guise of a story. Publishers have attempted to address this concern by using different labeling, fonts, colors, and other tactics to make the ads look different. But our findings show that no matter what steps publishers have taken, there is still significant confusion on the part of readers as to what constitutes an article and what constitutes an ad.

We surveyed 509 male and female consumers of varying ages (all of them 18+); what follows is a deep dive into how ordinary readers interpret native advertising that lives on publisher sites.

(This study is from 2015. Click here to read our more recent study on native advertising from 2016.)

Key findings on native advertising

- On nearly every publication we tested, consumers tend to identify native advertising as an article, not an advertisement.

- Consumers often have a difficult time identifying the brand associated with a piece of native advertising, but it varies greatly, from as low as 63 percent (on The Onion) to as high as 88 percent (on Forbes).

- Consumers who read native ads that they identified as high quality reported a significantly higher level of trust for the sponsoring brand.

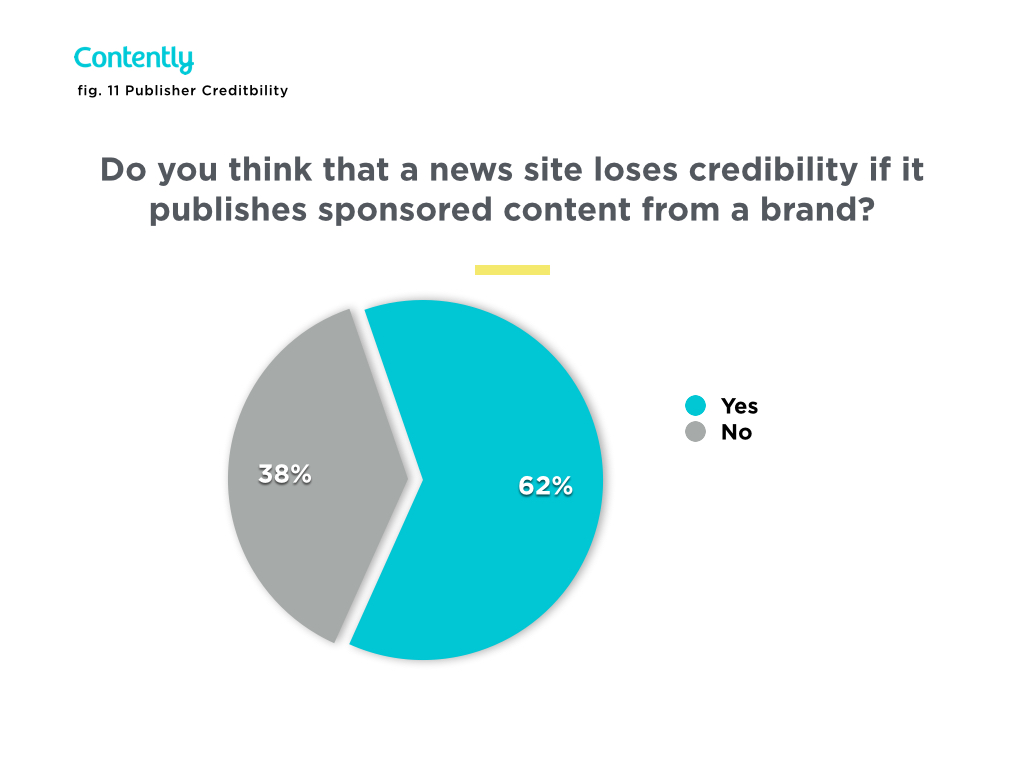

- 62 percent of respondents think a news site loses credibility when it publishes native ads. In a separate study we conducted a year ago, 59 percent of respondents said the same.

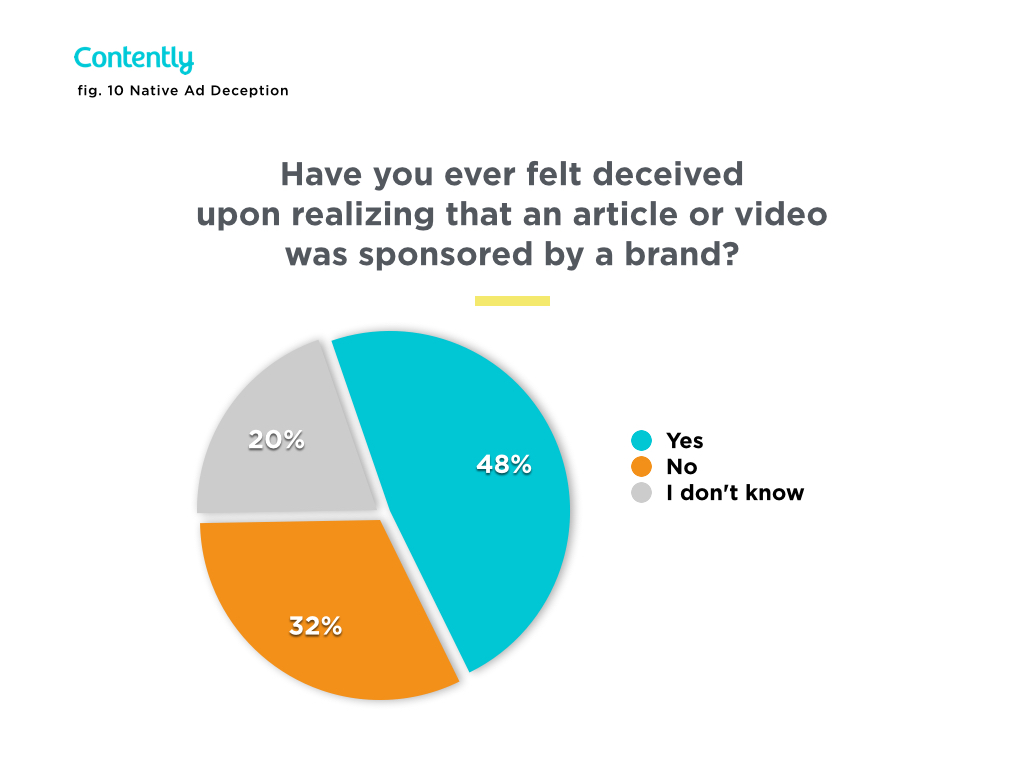

- 48 percent have felt deceived upon realizing a piece of content was sponsored by a brand—a 15 percent decrease from last year’s survey.

Methodology

We sought to understand one big question: Do consumers interpret native advertising as an advertisement or a published article?

We surveyed a total of approximately 509 consumers—a mix of males and females 18 years and older, balanced to the U.S. Census. Consumers were recruited via Research Now, a trusted global consumer panel provider.

We “talked” to them via a 10-minute online survey instrument created in Qualtrics. Each respondent was exposed to one sponsored content stimulus out of a possible six:

- This ‘Paid Post’ for Chevron that was written and produced by The New York Times’s T Brand Studio and lives on NYTimes.com. (81 respondents)

- This ‘Sponsor Generated Content’ for Mercedes-Benz that was created by The Wall Street Journal’s advertising department and lives on WSJ.com. (73 respondents)

- This ‘Sponsored Content’ for Raymond James that was created in collaboration by Atlantic Re:Think, The Atlantic’s creative marketing group, and Raymond James and lives on TheAtlantic.com. (71 respondents)

- This ‘Sponsored Post’ for Four Loko that lives on TheOnion.com. (71 respondents)

- This ‘Brand Publisher’ post for Miracle-Gro that lives on BuzzFeed.com. (72 respondents)

- This post for Citi published on the CitiVoice section of Forbes.com. (70 respondents) (Full disclosure: Forbes is a Contently client, and I once wrote and edited Forbes BrandVoice content, but do not any longer).

- This piece of editorial on Fortune.com, “5 Reasons Why It’s Great to Work at Whole Foods,” which was not sponsored by any brand and served as our control. (71 respondents)

Results and analysis

We were surprised by many of our key findings. In the interest of full disclosure, we’d like to share as much relevant data as possible—so apologies if you’re not a big fan of charts. The next few tables deal with pre-exposure brand awareness, recall, and rating. (If you want to skip to the really interesting stuff, scroll down three charts.)

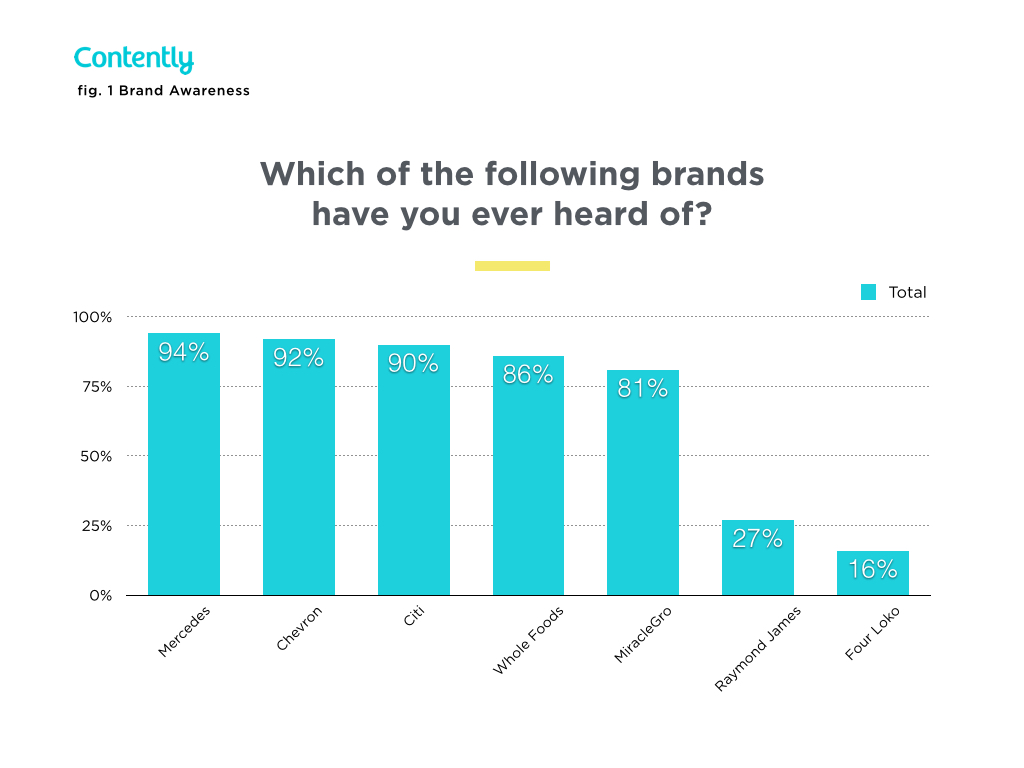

First, we sought to capture the brand awareness for each brand across each sponsored content group. Respondents were aware of most brands, although there was relatively low awareness of Four Loko and Raymond James.

Next, we measured pre-exposure brand opinion on a 1–10 scale. The overall opinion was about average for all brands; Four Loko rated somewhat above average, but that’s likely influenced by its low brand awareness.

We also wanted to capture pre-exposure brand recall as a baseline. Citi, Mercedes-Benz, and Whole Foods are the most recalled online. The majority did not recall seeing online ads for Four Loko or Raymond James, which makes sense, given their low brand awareness.

Respondents’ interpretation of whether a piece of native advertising was an article or an ad varied greatly. In four of the six groups shown a native advertisement, the majority interpreted the piece as an article. Respondents exposed to the Raymond James native ad on The Atlantic were nearly split: 53 percent said article, while 47 percent identified it as an ad.

In addition, respondents were more likely to identify the native ads in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and BuzzFeed as an article than respondents exposed to our control—an actual article about Whole Foods in Fortune.

So what are we to make of the fact that in four of the six groups exposed to a native advertisement, a strong majority identified it as an article and not an ad? There are a few possible interpretations:

- The most troubling view—and the one likely to be favored by native advertising critics—is that consumers simply can’t tell the difference between a native advertisement in any form and a regular article, and that their visual similarity is inherently deceptive.

- Then there’s the “devil in the details” explanation. This argues that there are flaws in each execution, and it’s the problems with design and labeling that lead to reader confusion (more on that after the next graph).

- Finally, you could posit that due to the deluge of content being thrown at consumers online at all times—ads, articles, videos, infographics, etc.—most people simply don’t bother to make much of a distinction. While those of us in media and marketing obsess over these details, to most consumers, it’s all just content, and they take it at face value.

(There are likely many other interpretations, and I’d love to hear them: lazer@contently.com or @joelazauskas.)

Next, we asked respondents who identified the native ad correctly to identify the sponsoring brand. (It’s worth noting that because so few people identified the native ads correctly, the sample size is pretty small.) Nonetheless, the data here is fascinating, since the degree and style in which publishers disclose the sponsoring brands of native ads is a topic of hot debate, and tactics vary widely.

The New York Times (83 percent brand identification) uses a sticky bar at the top of the post that identifies it as a “Paid Post” by Chevron and discloses in the text that the content was written and produced by T Brand Studio.

Forbes (88 percent) displays a prominent and expandable brand byline and bio.

The Onion (63 percent) indicates the sponsorship twice: “Presented By” above the headline and “Sponsored By” under it. Two Four Loko banner ads surround the content as well.

The Wall Street Journal (67 percent) identifies the sponsorship in relatively small print as “Sponsor Generated Content.” An additional disclosure states “Powered by the all-new 2015 C-Class,” and there is an additional blurb promoting the car.

Mousing over the “What’s This?” text explains the native ad in more detail.

BuzzFeed (86 percent) gives the brand a byline as a “Brand Publisher.” There is no overt indication that the post was paid for by Miracle-Gro. There are also embedded Miracle-Gro social feeds on fleek, as BuzzFeed would say.

The Atlantic (82 percent) has a disclosure of “Sponsor Content: Raymond James” that sits in the top-left corner of the page but disappears once you scroll 5 percent down the page.

Similar to The Wall Street Journal, mousing over “What’s this?” provides more details on the arrangement of the native ad.

Respondents were clearly more able to identify the sponsoring brand on Forbes, BuzzFeed, The New York Times, and The Atlantic than on The Onion or The Wall Street Journal, but from looking at the individual executions, it’s not immediately apparent why.

In addition, you might expect there to be a correlation between the share of respondents who correctly identified a native ad and those who could identify the sponsor of that same native ad, but that’s not the case. For instance, Four Loko/The Onion was the only native ad that a clear majority identified as an advertisement, yet it had the lowest sponsor identification rate. And only 29 percent of respondents who saw Miracle-Gro/BuzzFeed identified it as an ad (the second-lowest figure), but 86 percent of those who did so were able to correctly identify Miracle-Gro as the sponsor (the second-highest).

Let’s bring back those two charts to save you a scroll up:

As much as publishers insist that their native ad labels and disclosures are abundantly clear, it’s apparent that people remain quite confused.

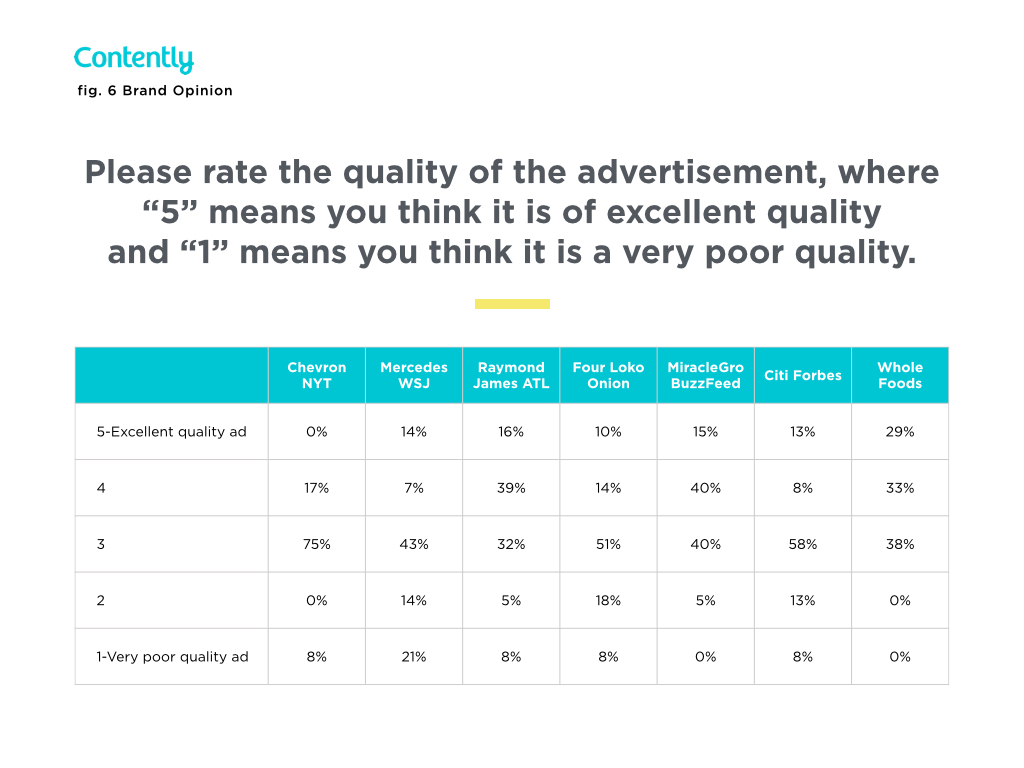

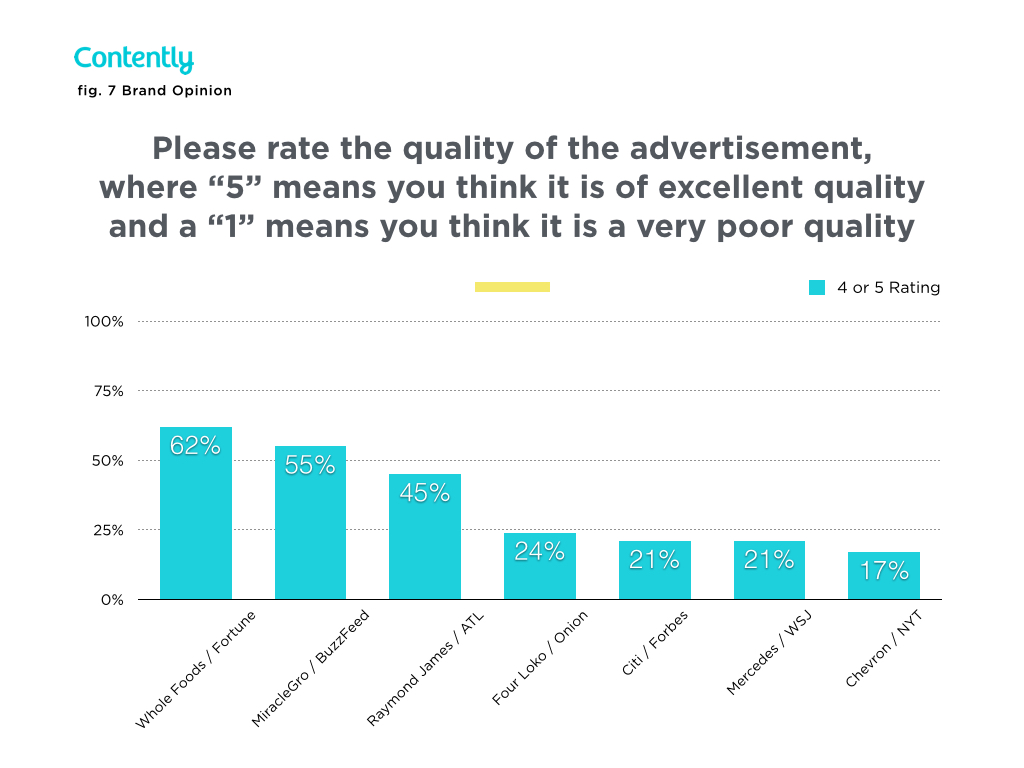

Next, we asked those who identified a native ad as an advertisement to rate the quality of the ad. We’ve included the full data for a deeper look, but also broke out what percentage of respondents rated the ad as either a 4 or 5.

Next, we asked those who identified a native ad as an advertisement to rate the quality of the ad. We’ve included the full data for a deeper look, but also broke out what percentage of respondents rated the ad as either a 4 or 5.

Among the native ads, Miracle-Gro/BuzzFeed’s listicle of “14 Hacks to Really Up Your Gardening Game This Spring” comes out on top with our respondents. Given the positive comments on the post, it appears BuzzFeed’s readers got real value from these gardening hacks. Raymond James/The Atlantic’s native ad, a detailed infographic on how baby boomers, Gen Xers, and millennials reach key life milestones at different ages, was also well received. Short, text-heavy, and relatively dull native ads for Mercedes/WSJ, Citi/Forbes, Four Loko/The Onion scored much lower. And despite a heavy dose of interactive charts that likely came with a hefty price tag, Chevron/The New York Times’s native ad received a lukewarm response. So did the Citi/Forbes native ad, in which Bruce Schlein, Citi’s director of corporate sustainability, details Kilowatt Financial’s partnership with the financial giant.

It’s here that we start to see a directional pattern.

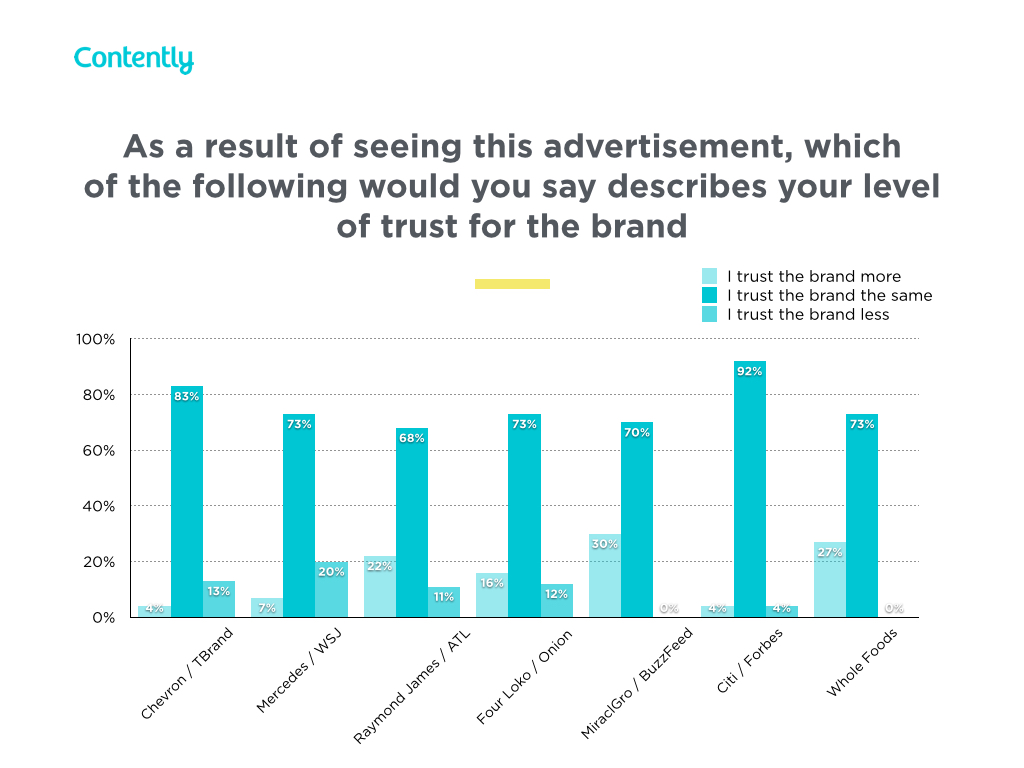

By and large, the native ads that were rated as higher quality drove more trust for the sponsoring brand; those that were rated as lower quality drove less brand trust. Miracle-Gro saw a 30 percent boost from its native ad, and Raymond James got an 11 percent bump. Meanwhile, Mercedes lost trust from its poorly rated native ad, and the lukewarm response to Chevron’s native ad corresponded with a loss in trust as well. Four Loko and Citi saw little or no gains.

Another interesting point to note: The control article, Fortune’s listicle of “5 Reasons Why It’s Great to Work at Whole Foods,” is the best kind of earned media a brand could hope for. Pretty much every company in the world would be thrilled if Fortune wrote about why it’s great to work there. (Particularly Amazon at this very moment.) And it sure delivers: 27 percent of people who read that article said they trusted Whole Foods more as a result.

It appears that native advertising, when well executed, can have the same impact. Thirty percent of people who read Miracle-Gro’s native ad on BuzzFeed said that they trust the brand more.

Interestingly, this doesn’t totally match up with how people responded when asked if they trust sponsored content, regardless of who sponsors it:

Ultimately, it appears that the context and execution of native advertising has a huge impact on consumer trust. While most say that they don’t trust it as a concept, that doesn’t necessarily hold for individual ads, as long as they are done well.

Nonetheless, the widespread confusion displayed by respondents in this study should give the industry pause, as should the next two graphs. As noted in the key findings, nearly half of all respondents have felt deceived by sponsored content in the past, and nearly two-thirds think that publishers lose credibility by running it.

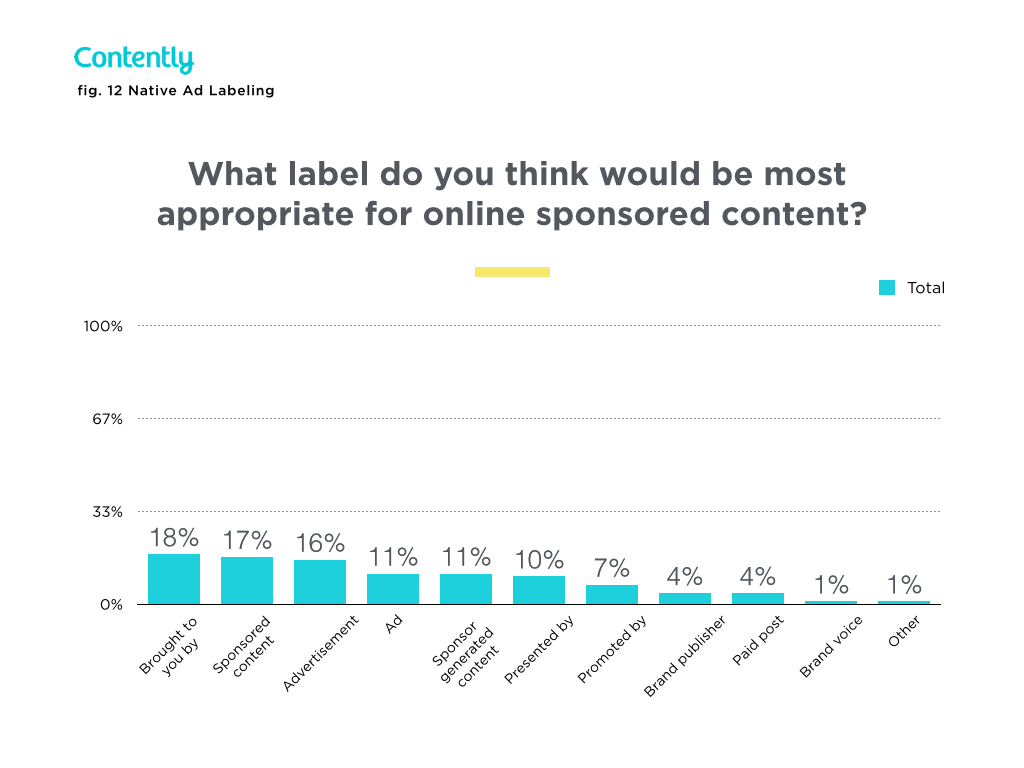

While much of the debate in the media echo chamber focuses on correct labeling as the key to earning consumers’ trust and disclosing native ads properly, it doesn’t appear that consumers actually have a preference.

The Future of Native Advertising

In last year’s study, we concluded that sponsored content has a long way to go. That still appears to be the case. When it comes to native advertising, consumers demonstrate clear confusion in interpreting it as an article or an ad, and struggle to identify the sponsor. This should make brands and publishers alike reevaluate their execution of this popular new ad format.

Native advertising is a complicated problem to solve. A year ago, we identified labeling, brand self-promotion, disclosures, and quality as pain points, and pointed to BuzzFeed and The New York Times, in particular, as models for the industry. But while those publishers’ native ads certainly performed better in terms of sponsor identification and trust earned than other publishers, there still appears to be a fair amount of confusion. Overall, consumers’ opinion of native advertising is fairly negative.

However, as BuzzFeed and The Atlantic’s ads show, there’s still potential for native ads to drive a lift in brand trust if the native ad fits contextually and delivers a lot of value. Brands would be smart to invest in the native ads on publisher sites that drive those kind of results.

We’d call for brands and publishers to push to make disclosures of brand sponsorship even more pronounced, and hold a high standard of value that they’re delivering to clients. Native ads still have potential (and they’re certainly better than banners), but they’re a long way from being perfect.

Image by ShutterstockGet better at your job right now.

Read our monthly newsletter to master content marketing. It’s made for marketers, creators, and everyone in between.